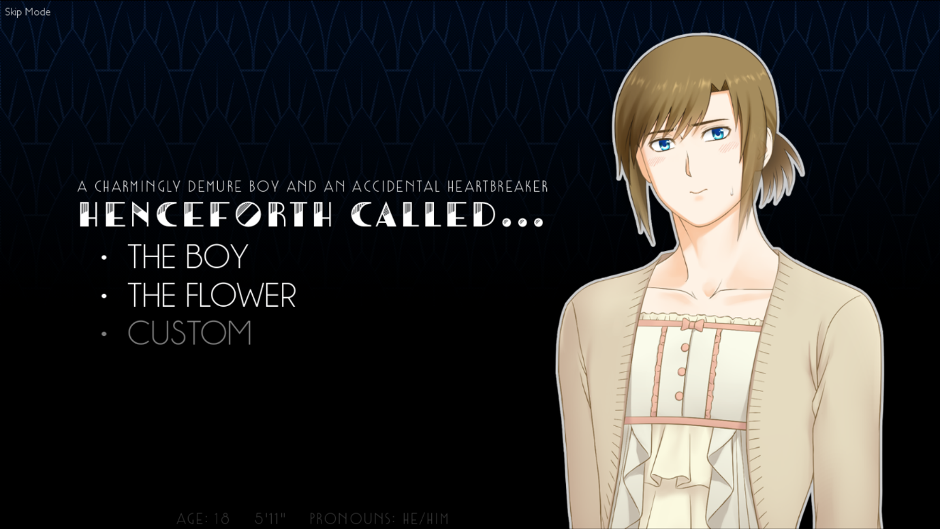

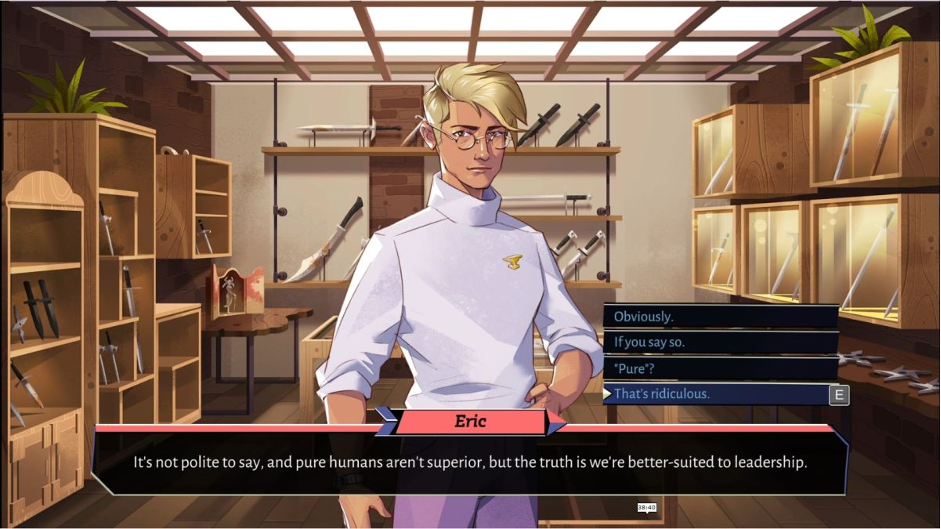

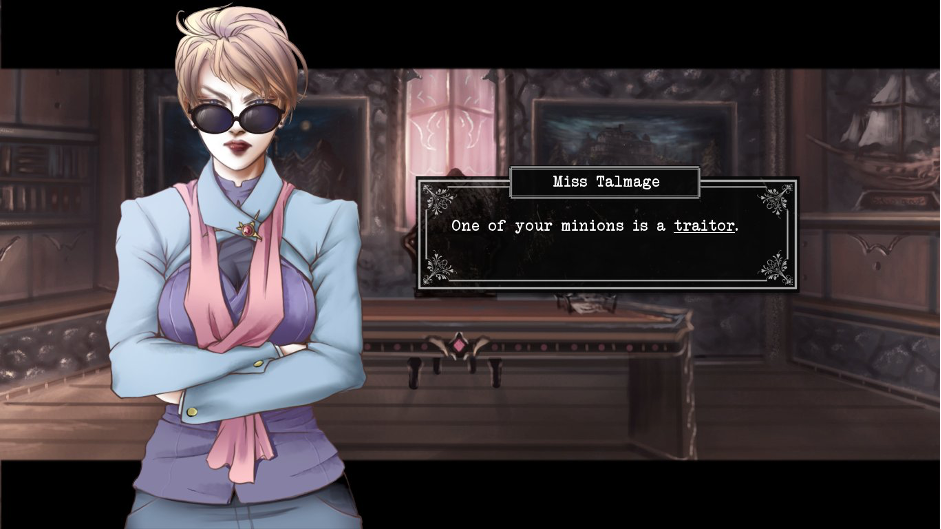

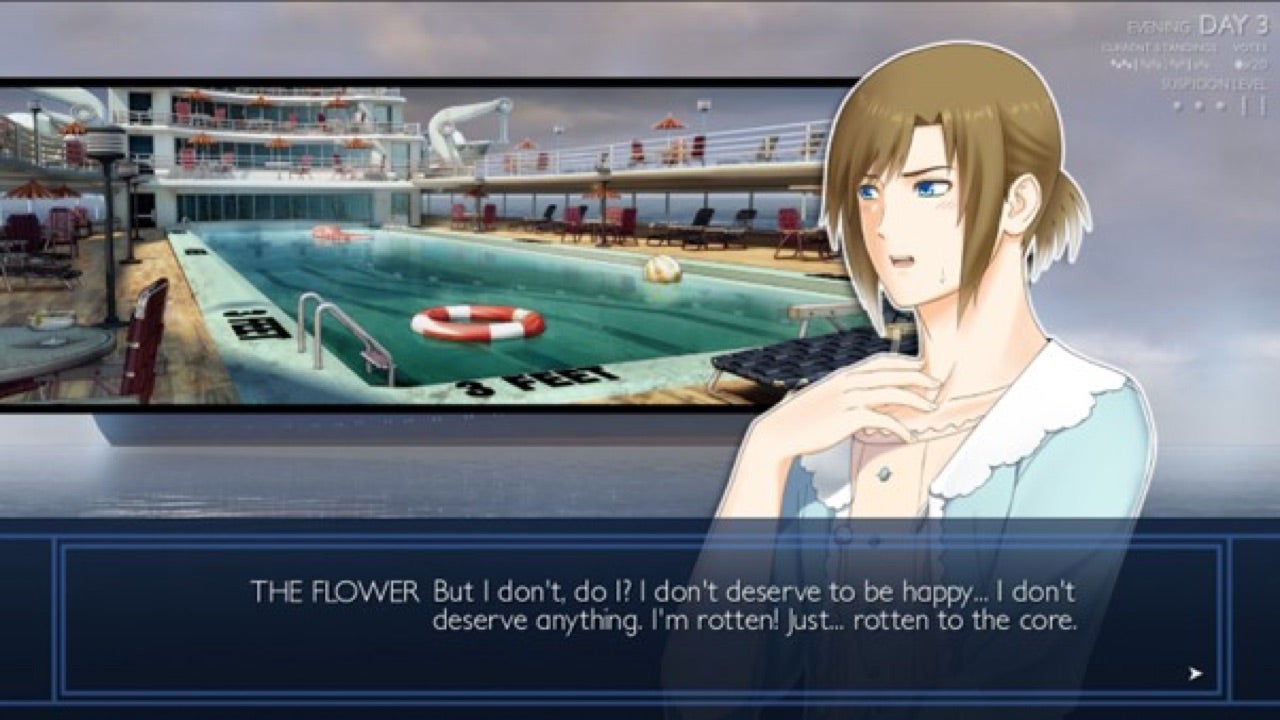

When I changed my name to Elia in 2021, the first game I ever played using my new name was Christine Love’s visual novel Ladykiller in a Bind. Knowing very little about the game, and given my lifelong affinity for my fellow effeminate brunettes, I gave my new name to this character: I assumed he’d be a sweet, queer character and I’d be able to relate to his storyline. As it turns out, minimising spoilers, The Boy is actually a manipulative, pathetic object of contempt with precious few humanising moments. So, now that’s my guy. Go figure. But my relationship to The Boy – and my dislike of how he’s written – has made me think a lot about complicated queer games, representation, and what queer people want from queer media. Queer people are an essential part of gaming culture, both as players and as creators, but our position in popular gaming culture is still precarious. Games that give us any leeway to be gay whatsoever still feel like a gift. (I am doubtless not the only mid-2010s teenager who came to gayness through making entire cities of lesbians in The Sims Freeplay.) So, whenever we encounter a bad gay – a gay who is just a real piece of shit, and sometimes not even in a Lady Dimitrescu crush-my-neck-mommy kind of way – or a queer game that intends to make us feel uncomfortable and unsettled, there tend to be a lot of mixed feelings about it. And that makes sense! We’re a little starved for game representation; it can feel frustrating to yearn for a character into which to pour your empathy and sorrows, and to instead be presented with an exasperating dickhead. But I’m increasingly drawn to tricky and dark queer games more than the fluffy, wholesome kind. I’m not a tentative beginner gay anymore; my desire to feel hugged by a game is less than my desire for it to recognise me and fuck with me. I want pain and transgression in a controlled environment. To put it bluntly: I want the final boss to forcefemme me, and if they won’t, I will make them. (Please don’t Google that.) Basically, when queerness is divorced from ethical action and moral representation, you get to explore queerness as sexy and insurgent, and also as co-optable by authoritarian and fascist causes. Good games about bad gays are rarer than I’d like, but I have some favourites. One is another visual novel, Black Closet, in which the fun romancing of pretty women characters is complicated by the fact that you’re an awful person running an in-school authoritarian cop squad and some of those pretty women are trying to sabotage you. Another is Paradise Killer, a neon-drenched nightmare in which you play a bisexual member of a mass-murdering God-cult. I also like games like Night in the Woods, in which many of the characters are queer, and their queerness neither causes nor alleviates most of their problems. Ladykiller – which follows a bunch of attractive Machiavels manipulating each other for fun and profit, including the protagonist, a lesbian disguising herself as her twin brother – is mad, messy, hot and ambitious, and a great fantasy space for exploring power and desire. It’s about how our desires for safety, pleasure and emotional connection coexist with riskier desires to deceive and be deceived, to use others and be used, to gain power or be confronted by it. But it’s also been dogged by controversy within the queer community since it launched, particularly due to a now-edited scene involving its lesbian protagonist being sexually humiliated by a man, and making sense of that controversy – what to take from it and what to leave – requires understanding queerness on deeper levels than ‘hey, this game has some cute lesbians in it.’ Some of Ladykiller’s reviews cringe at its deceptive main character and its mildly sexualised sibling relationship and its depiction of scenes of dubious consent, lacking a wider context for why those things are central to queer sexual fantasies. The siblings are improbable doubles of each other, there to create opportunities for sexualised gender-play, plus lesbians have a playful relationship to siblings in fiction because there’s scarcely a lesbian in existence who hasn’t had her girlfriend confused for her sister. As for deception, given how trans people are wrongly and violently accused of deceiving cis people by existing as trans, there’s a reason we’re drawn to masquerade fantasies. These grey areas of fantasy are produced by our need to work through the violence in our real lives, and to turn it into gratification. The desire to turn them into safer, cleaner representation is a flattening desire. But when I was reading The Boy’s narrative in Ladykiller, I felt bad, and I had to puzzle my way out of that: is this guy just an asshole and I feel weird because I wanted to be validated by him? Does a game owe me that? The answer I eventually came to is that The Boy, whose storyline is mainly wrapped up in pining for another guy and then blackmailing the protagonist into a deeply uncomfortable sexual encounter, isn’t given the same sexual agency that enables the other characters to be interesting and rounded. While he’s desired by other characters, he feels passive in the face of that desirability, and the fact that the game has so much more to say about the fun and power of masculine lesbianism than feminine gayness was disappointing, to me. The logic behind his characterisation feels flawed and skewed in relation to the rest of the cast. But there was something satisfying in experiencing a tricky queer storyline that I disliked, even. I didn’t dislike The Boy because he’s a bad gay and I want to be a good one; he’s part of such a rich and ambitious text that I had to fight my way to a complicated rationale for why he might be presented unfairly, and what makes Ladykiller’s other bad gays more well-rounded and compelling. The same goes for the game’s cut content and controversial ’transactional sex’ scenes, which I still haven’t made up my mind about. One person might find those scenes violating, while another might find them productively risky and insightful. In a time where minorities are harassed as engaging in ‘cancel culture’ for wanting to disengage with media that insults and degrades them, it’s been made artificially difficult to talk about the joys of challenging art. We need games that are ambitious and complicated enough to do things wrong in interesting ways, and for games that divorce queerness from a demand for good representation and ethical practice. We also need ample space for games criticism that is chewy and conflicted and personally invested, and that is willing to make a case against a game’s choices without pushing the most marginal and risky art out of our spaces. Ladykiller is a game that I keep coming back to, keep testing my teeth on, keep pressing and pulling at and replaying. I played Gone Home once and found it sweet; I go back to Hades every so often, trying to juice more out of its gay storyline than it will give me; but it’s games like Ladykiller and Paradise Killer and Black Closet that stick with me, with their questions and their problems and their commitment to examining the spiky and complicated shapes desire can take. I hope that in the coming years there are far more tricky games about bad gays that are given a public platform, and that both queer creators and queer critics are given space and pay to formulate their arguments and negotiate with each other, rather than being demanded to be simple and good, to exit our discomfort, and to take up as little space as possible.